Don't Ask. Please Do.

This week, I made my annual migration, returning from our house on the island to our 21st floor apartment on Chicago’s Near Northside. I traded the morning chorus of raucous crows, nattering red squirrels, yodeling loons, diesel-thumping lobster boats on the Bay, the occasional eruption of a chain saw somewhere down the road for the clamor of ambulance sirens, taxi horns, air hammers tearing up the curbs at the corner, the bump and grind of garbage trucks in the alley below. I traded our island and peninsula farmers’ markets for the City Green Market, and Burnt Cove, Mainescape and Tradewinds for Plum Market, Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods. I traded, too, our house’s view of the Bay pocked with islands, white sails and boat hulls punctuating blue, the distant Camden Hills, and an expansive cloud-dolloped sky above for this apartment’s urban vista of squat and tall buildings, rooftops and steeples, of cars and buses and yellow taxis on the gridded streets of myriad neighborhoods stretching west toward the distant looping expressway and the planes near O’Hare dotting the horizon.

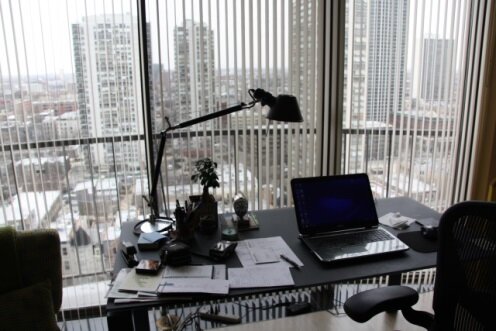

But the late afternoon light seems almost the same – both places, interestingly, face due west – and it cascades over my windowside desktop with an easy and welcome familiarity. Atop my desk, transported here in bins packed into my car, are the same file folders and notebooks, the clamped, printed-out, copiously scribbled upon 50-plus pages of what I’m hoping will be my new book. And, unfortunately, about that, the question is the same here, too. “What are you working on?” my friends and family ask.

Okay, I know most folks ask out of true interest. Many have read my previous books and want to know: What’s next?

But here’s the rub: Ask your writer friend, just a month or two in, to describe what she’s working on, and chances are she’ll once again discover that nothing damages a book in its infancy more than trying to describe it. Still, because she’s your friend, she’ll try. If it’s a work of non-fiction, as mine is, perhaps she’ll stick to, or try to, the book’s About-ness. “Well, it’s about the time period when….” Or “I want to tell the story of my brother and mother by exploring….” Trust me, she’ll likely stammer, speak in incomplete sentences, possibly even become incomprehensible as she loops back to where she began, reaching for words that won’t come, distracted as she’s become by listening to the air leak out of the balloon, to how, by sounding like a blithering idiot, it’s clear her new book is going nowhere, was a stupid idea in the first place, and is, surely, doomed to failure.

This is partly because, as noted by Mark Slouka in a recent New York Times piece, no time is as fraught for writers as those first few months of uncertainty, “that miserable time when we think, believe, know with absolute assurance that we’ve found the key to the book in our hands, though maybe, probably, definitely not.”

Uncertainty can be a good thing for a writer. Even essential. It’s where we start from and is often a catalyst. As the late fiction writer Grace Paley once claimed, “we write about what we don’t know about what we know.” And in the beginning, there’s a lot of not-knowing. Plus we’re unsure. Of, says Slouka, nearly everything.

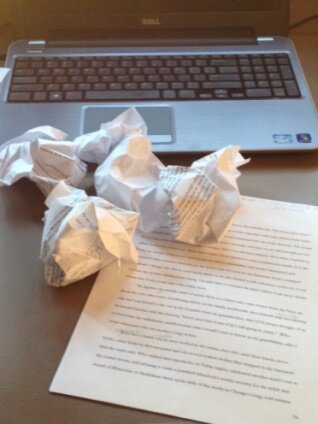

Let’s say one day I’m stuck. I sit down in the morning but hours later have nothing worth keeping to show for it. That can only mean I’m spinning my wheels and the new book is a disaster. My inner critic steps in and tells me I’m no good at all, or only as good as my last paragraph which, as it turns out, was written, what, two days ago? And here is when it’s especially bad news if someone asks: “So what are you working on?” Or, worse: “How’s your new book coming along?”

In a Paris Review interview, Ernest Hemingway once said, “There is one part of writing that is solid and you do it no harm by talking about it, the other is fragile, and if you talk about it, the structure cracks and you have nothing.” In the early going, it’s all fragile, or so it seems to me.

So, don’t ask means don’t ask. Except.

Except most writers also want validation. Hemingway is to have said writing is a private, lonely occupation with no need for witness until the work is done. But that was Hemingway, one of our most acclaimed American writers, talking. The rest of us may indeed need a little witness. Don’t ask but….

The naughty truth: we don’t want to talk about what we’re working on and we crave affirmation. Deep down, we want someone to read our words and tell us they – we – are brilliant. Or, okay, that at least we’re on to something. And so, yes, keep going. Indeed, please, you must keep going and finish your book. So, possibly, we succumb. We recruit a willing reader and hand over a few pages accompanied by the requisite warnings that they’re only part of a first draft, that it’s all still so early, that things may change…yada yada yada. Perhaps from our reader we get an enthusiastic thumbs up. But then, a few days later, stuck again, blundering about in the dark, it becomes clear – that reader knew nothing. Things are as bad as we suspected.

I pity my poor husband Bob. Over our many years together, he’s had to learn that when I’m thick into something new, “How was your day?” has dangerous subtexts. Generally, he now waits for my cues. “I had a good day,” I might say as we sit down to watch some news before dinner. “Oh, good. How so?” he might respond, distracted by the breaking, somewhat worthier news that a government shutdown is imminent or bombing Syria is a real threat. Otherwise, he would know how easily “How so?” can morph into the question that dare not speak its name. (Okay, a little extreme, that.) Other times, he doesn’t need to wait. I leap at the chance. “Today was awful. I’m getting nowhere. This supposed book is a huge mistake. A waste of my time.” To which, indefatigably supportive, he says something like, “You’ve had these episodes before. You’ll get over this hump.”A mere hump? Really? Cheerleaders waving poms poms are so clearly on the sidelines. But I do give him immense credit when just days later, should I affirm, “I think I’m onto something,” he never says “See, I told you so.”

Bottom line: I’m more or less in agreement with Hemingway. About my new book-in-progress, all of which still seems to me like such a fragile thing – I don’t want to talk about it (much). I also don’t need witness (most of the time). Especially now, in the early going, when the visioning needs to be uniquely my own. Later, of course, I’ll be the one asking the questions, when I can – and need – to trust one or a handful of folks who will give it to me straight.

Meanwhile, butt in chair, I write. About what, dear friends, don’t ask. Really, (right?). Don’t.